I’m always struck by how successful we have been at hitting the bull’s-eye of the wrong target. I mean we have learned- for example, in cattle we have learned how to plant, fertilize and harvest corn using global positioning satellite technology, and nobody sits back and asks, “But should we be feeding cows corn?” We’ve become a culture of technicians. We’re all into the how of it and nobody’s stepping back and saying “But why?”

Joel Salatin in “Food, Inc.”

Mainstream development eonomists look to the history of the US and Europe as a model for all countries to follow, believing societies evolve in a linear fashion. This applies to the agricultural systems as well-they pass through a set of stages from small scale, traditional and unproductive to large scale, modern, and efficient. Just as industrialization helped US and European economies grow, so too will it help poorer countries today.

What’s more, they believe economic growth can lead to environmental stability, seen in what is called the Environmental Kuznet’s curve. Intensified agriculture, then, will help help decrease environmental degradation. 50 years after the purported success in Asia people are calling for a Green Revolution in Africa, as the New York Times argued just last year in an op-ed. http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/04/09/a-green-revolution-this-time-for-africa/ It is seen as solving both economic and social problems.

However societies do not evolve in a linear line. There are many ways of seeing the world, as we read in Chronically Unstable Bodies; where European-descendent societies have a clear dichotomy and hierarchy between nature and culture, environment and economy, Wari’ society does not operate under the same human-nature divide. Imposing European history onto every society masks the diversity of human culture

panna.org

Even in Western countries the reality of industrialization is much less optimistic/rosy than pictured above. Industrialized agriculture has many hidden costs and long term negative effects.

This form of agriculture typically relies on monocropping-growing one crop exclusively-and export agriculture to facilitate economic growth. While more “efficient”, relying on one main crop for export means among other things relying on global commodity prices, becoming vulnerable to price changes and putting small farmers into competition with large agribusinesses. It is a risky model. Robert Todd Perdue and Gregory Pavela point out the pitfalls of relying on a single resource in their article Addictive Economies.

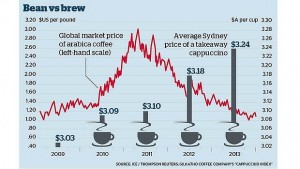

Agricultural products are no different, varying widely in price over time. For many the trend has been to decrease. Average prices for coffee, for example, are substantially lower than they were 60 years ago, meaning farmers earn less and less for more work.

Industrial agriculture, in its quest for efficiency and economies of scale, favors large farms over small ones, exacerbating inequality around the world. Most agricultural profits are in the hands of a few large multinationals; Cargill, Monsanto, DuPont. Despite the importance placed on free trade these companies owe their low prices and large profits to huge government subsidies, as Brewster Kneen shows in The Invisible Giant.

OUR GOAL: to reduce hunger and poverty for millions of farming families in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia by increasing agricultural productivity in a sustainable way.

Organizations such as the Gates Foundation place a big emphasis on agricultural development to reduce hunger and poverty. Although they emphasize sustainable agriculture and partnership with local people they still operate under the assumption of the superiority of Western knowledge.

Browsing their website you see pictures of smiling farmers, and talk about taking local views into account. However you do not see any mention of working with local people as partners, or of implementing projects designed by local people.

The mentality here is similar to that of many development organizations, that “wildly disparate” problems can be solved by benevolent wealthy Western businessman whose authority comes from them being wealthy, white and successful in business. In treating hunger and poverty as a global problem which they have the opportunity to solve they [obscure] any culpability they may have in [furthering] an unjust economic system. The tendency to talk about “global” environmental problems was discussed by Peter J. Taylor and Frederick H. Buttel in How Do We Know We Have Global Environmental Problems?

And-though you won’t see this on their website- they are supporters of agricultural giants like Monsanto and Cargill, companies that certainly do not embody environmental or cultural sustainability